Today, I have a radical suggestion for the average Joe Masters (if not the highly trained and young, elite athlete) — and face it, that certainly means me and probably a lot of you: every once in a while, go for a brisk walk instead of a long run.

Very careful readers of my blog already know of my high regard for taking a walking break when going on a long run and here are two good arguments:

- Evolutionary: humans are the best endurance runners in the animal kingdom but when going for a day of persistence hunting with our buddies in the African Savannah 100,000 years ago, we very likely took a walking break every once in a while (if for no other reason than finding the animal again which was taking a break)

- Biomechanical: endurance running is a repetitive movement that puts a lot of (eccentric) load on our muscles, bones and connective tissue. Taking away the stress even for a short period by walking for less than a minute has the power to prevent a lot of overuse and injury

But now I argue for adding entire walks rather than another run for the average masters athlete (for clarification, I am not talking about the overweight couch potato wanting to slowly ease into exercise again but about you: the active masters athlete training regularly and following a plan).

My key insight (and subsequent changes to my training regimen) came from two scientific papers:

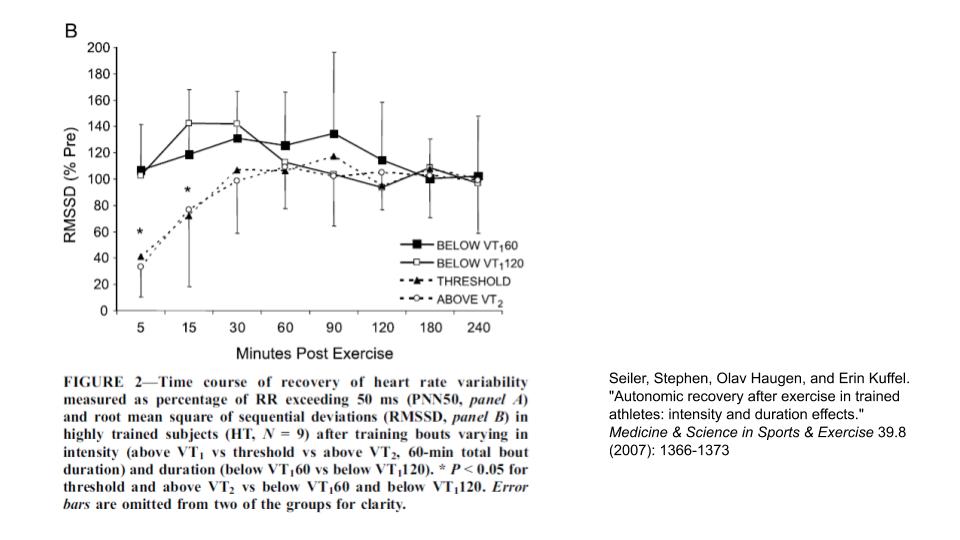

The first insight came from a classic paper by Stephen Seiler, the great scientist and generous popularizer of polarized training. In the paper, the authors describe that if we want to accumulate those many hours to build our aerobic base, the ventilatory threshold I (below which we can carry on an easy conversation) is the break-point for autonomic nervous system disruption. Below it we are fine and recover very fast, but above we do not recover fast independently of how intense the effort above the VT1 is (which supports the key argument for avoiding Zone 2/threshold training as the cost is as high as for HIIT but the pay-off is less).

As masters athlete of course, the limiting factor to our training volume is most likely our ability to recover (not our willingness to do more).

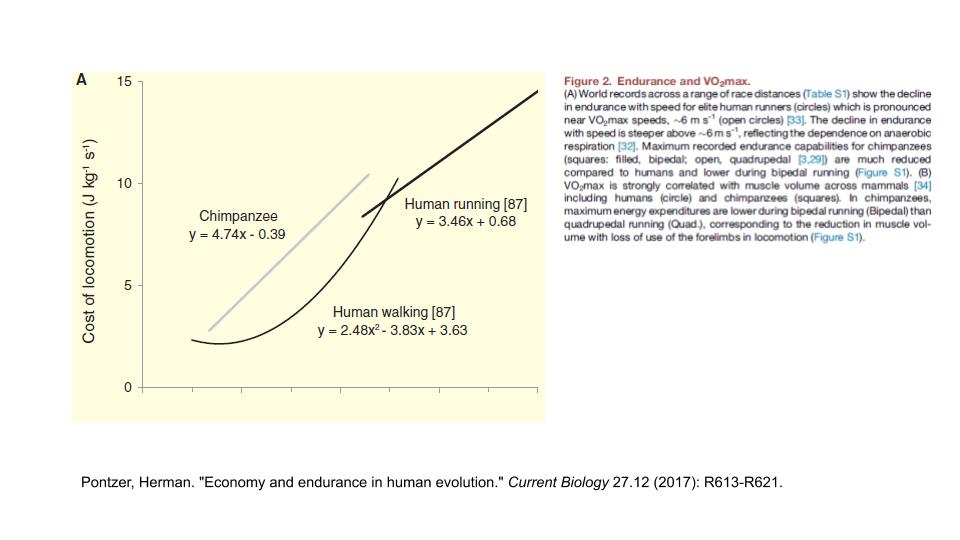

The second key insight for me came from a review on the evolution of humans as endurance runners. In it, there is a nice chart (see below) comparing the energy cost of human running and walking.

The cross-over is at around 9 J/(kg*sec). One milliliter of oxygen yields around 20 J so this equates to around 27 ml 02/(kg*min). If you want to make sure that you train in Zone 1, you should be at around 60% of VO2max. If you train at the brisk walking pace of 27 ml 02/(kg*min) and want to be at 60% of VO2max, your VO2max should therefore not be more than 45 ml o2/(kg*min).

Are you still with me? A V02max of 45 means you run a little more than 2,500m in the 12 minute Cooper test – and I bet that many of the joggers that I see in the woods during my regular runs do not.

For me it served as a nice reminder of how psychologically hard it is to stay in Zone 1 for an entire hour while running when every other runner is an invitation to pass and every hill is one to jack up your heart rate. The litmus test is going home and seeing if your heart rate variability (HRV) score returns to normal within 30 min after your work-out. If you go for a walk instead, you are safe as it is virtually impossible to leave Zone 1 unless you are going steep uphill.

What happened to me as I started to incorporate brisk walks into my training routine?

First, I did not stop running but just added walks on my resistance training and off-days and never felt tired as a result.

Even better, I incorporated a lot more hours in Zone 1 without any overuse injury risk and should not have been (but still was positively) surprised that my base HRV score improved as well. Why not give it a try yourself?

Bonus for Sports History Buffs

… the Finnish runners began their walking training in January or February, depending on the distances they raced. […] The distances walked also depended on the distances the runners would race; marathon runners walked longer distances (15 to 35 km) than did the 1,500m runners (8 to 15 km) and the 5,000- to 10,000 m runners (10 to 20 km). Each group would walk these distances two to four times per week until the end of March.

The Finnish Training Methods of Kohlemainen and Nurmi (page 376, Noakes, Timothy. Lore of running. Human Kinetics, 2003.)