If aging is the loss of dynamic homeostatic capacity (i.e., your reduced ability to deal with changes in the environment) can you attach a number to it to know where you stand?

Fortunately, you can and it is called heart rate variability or HRV. Heart rate variability has two great advantages (1) it is a highly integrated and meaningful measure and (2) it is super-easy to measure (at least today).

Before going into why it is meaningful and how to measure it, here is a very brief introduction into what it measures.

What is heart rate variability?

Heart rate variability is a measure of the variation in time between your heartbeats. Your heart is not a drum machine and does not keep a constant timing. Indeed, more differences between heartbeats (i.e., a higher HRV) are in general beneficial and a measure of good health. There are many ways of expressing your HRV but the most common is a statistical measure called the rMSSD (root mean square of the successive differences) which you will most often find displayed on consumer applications. When explaining what it actually measures you most often hear that it reflects the balance between your sympathetic nervous system (speeding up) and your parasympathetic nervous system (slowing down). While its sound attractively ying-yangy and is kind of true, I advise to either (1) ignore trying to understand it physiologically and instead focus on what it means below or (2) actually go a bit deeper and discover that it actually is a bit more complicated and of a higher order of integration that goes beyond heartbeats alone.

Why is HRV meaningful?

Clinically, HRV scores are used in cardiology and other medical disciplines as a risk stratification tool. Poor HRV score is an early predictor of poor outcome in coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, arterial hypertension, sudden death, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, heart failure, diabetes, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, leukemia, obstructive sleep apnea, epilepsy, headache and others. This is consistent with the view that HRV measures how well you deal with disruptions and your ability to return to homeostasis.

Equally important, HRV scores decline with age also consistent with our definition of aging as reduced dynamic, homeostatic capacity.

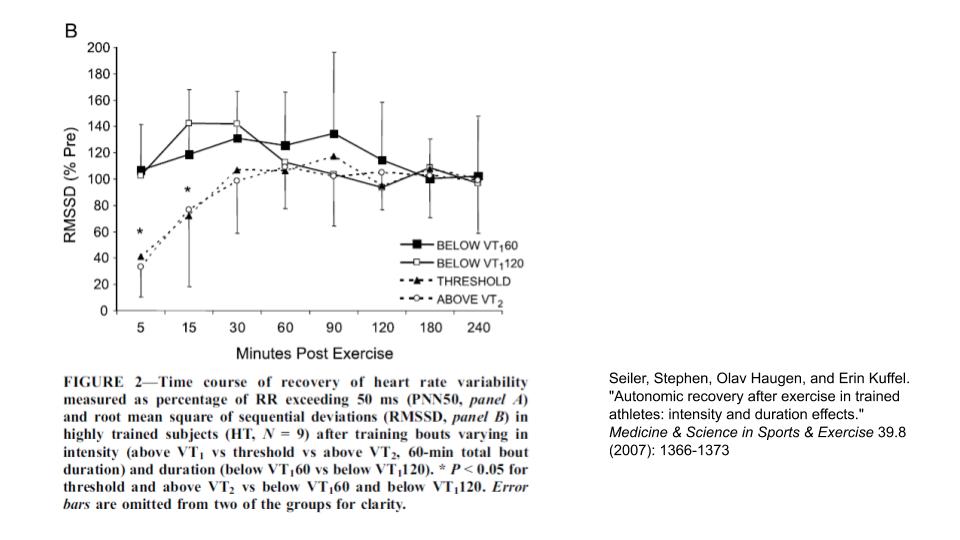

Also, HRV scores have been used as proxies for positive training adaptations and most prominently as tools for load and recovery management. Simply spoken, you are ready to hit it hard again once your HRV has returned to your base level and better athletes recover faster.

So how do you measure HRV?

It is as simple as downloading an application on your phone and holding your finger on top of the camera for a short period of time (some apps are free, some are not).

What you will discover when starting to measure HRV is that it varies quite a bit an so it should. Therefore, it is important to establish a baseline by measuring under similar conditions (e.g., sitting or lying down) at the same time of the day (e.g., right after getting up and before reading your email) as both stress and circadian rhythm affect HRV scores.

How do you improve your HRV score?

And now the fun starts as you can experiment with all the things effecting both your base score as well as your HRV recovery after exercise. If you have been reading any of the other articles in this series, you will not be surprised that you should optimize successful aging (which will then improve HRV) and we already know how to do this in general: exercise, keeping insulin low (fasting/reducing carbohydrates/increasing muscle mass) and sleeping properly/reducing chronic stress. Please remember to only compare yourself to yourself over time and not to others. You do not win a prize for having the highest HRV in the universe but for keeping or even better improving yours over time.

So let’s play with individual interventions (here are some that I have tested):

- How honest am I with my easy sessions? Are they really easy enough so that I recover my HRV base within 30-60 minutes?

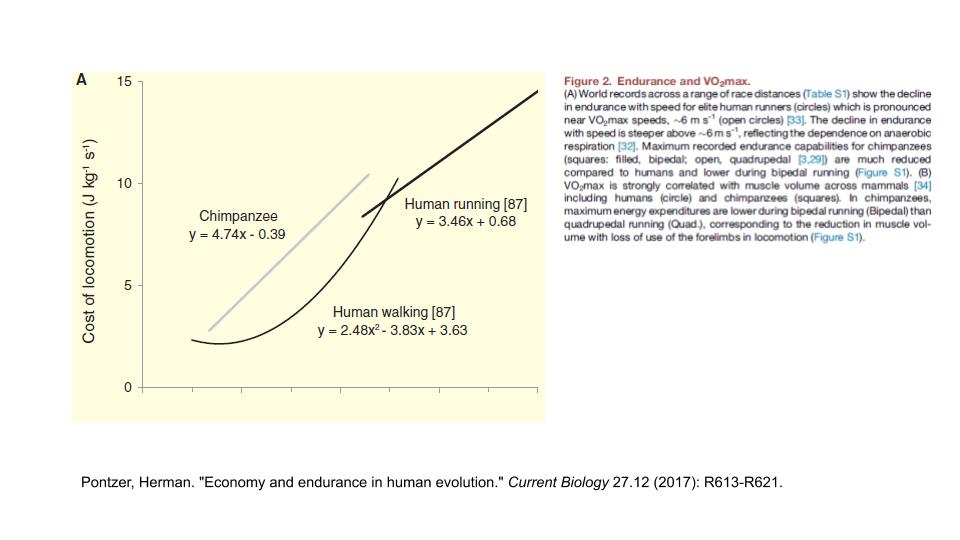

- How come walking is so effective in improving base HRV even if it is below even Zone 1 levels of exertion?

- How honest am I about acute and chronic stressors such as alcohol – does dry January help in improving base HRV?

Fun Bonus Episode

Flying into space improves your HRV and the effect is likely to be anti-aging for humans and proven to be life-extending for worms (C. elegans).

Surprise again (not): when they analyzed the genes down-regulated in space that are likely to be responsible for the anti-aging effect, they found the insulin equivalent in worms as well as others involved in dietary-restriction signalling.